Even though, hair texture not only can vary within individuals but also can even vary on different parts of the scalp, all of which create unique combinations or variations of these textures, hair can be basically classified into 4 main types (straight, wavy, curly or coiled/kinky). And in this article, we will discuss further about kinky – also known as Afro-textured hair whose strand grows in a tiny, angle-like helix shape.

Additionally, the goal of this article is not just only provide detailed information in terms of terminology and styling of this hair texture, but also celebrate the resilience, diversity, and identity of individuals within the African diaspora through its related historical context, cultural significance and the journey towards self-acceptance and empowerment because hair is not just a physical attribute; it carries more than that!

Terminology

The term “woolly”, “kinky”, or “spiraled” has historically been used in the English language to describe the natural texture of afro-textured hair. In a more formal context, the word “ulotrichous” has been employed to refer to curly-haired individuals. The term originates from the Ancient Greek words “οὖλος” (oûlos), meaning “crisp” or “curly,” and “θρίξ” (thríx), meaning “hair”. Its opposite, “leiotrichous”, describes individuals with smooth hair. In 1825, Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent introduced the scientific term “Oulotrichi” for the purpose of classifying human hair types within the field of taxonomy.

In year 1997, hairstylist Andre Walker introduced a numerical grading system to classify different human hair types [2]. This system, known as the Andre Walker Hair Typing System, categorizes afro-textured hair as “type 4“. The system also includes other hair types such as type 1 for straight hair, type 2 for wavy hair, and type 3 for curly hair. Besides, letters A, B, and C used as indicators of the degree of coil variation in each type. Within type 4, the subcategory of 4C is considered most representative of afro-textured hair [3]. However, it is important to note that afro-textured hair can be challenging to categorize due to the wide range of variations among individuals. These variations include the curl pattern (typically tight coils), the size of the curl pattern (ranging from watch spring to chalk), the density of the hair (from sparse to dense), the diameter of individual strands (fine, medium, or coarse), and the overall feel of the hair (described as cottony, woolly, or spongy) [4].

Observable differences in the structure, density, and growth rate of hair can be attributed to genetic variations among different ethnic groups. While all human hair shares a common chemical composition primarily made up of keratin protein, there are specific characteristics that differ across populations. Research by Franbourg et al. has indicated that black hair may exhibit variations in the distribution of lipids within the hair shaft [5].

When it comes to density, classical afro-textured hair has been found to be less densely concentrated on the scalp compared to other hair types. On average, the density of afro-textured hair is approximately 190 hairs per square centimeter, which is notably lower than the average density of European hair at approximately 227 hairs per square centimeter [1]. These findings highlight the variations in hair density among different ethnicities. Loussourarn’s research revealed that afro-textured hair grows at an average rate of approximately 256 micrometers per day, while European-textured straight hair grows at a faster rate of approximately 396 micrometers per day [1][6].

Another unique characteristic of afro-textured hair is its tendency to experience “shrinkage.” This phenomenon occurs when kinky hair, which appears to be a certain length when stretched straight, appears significantly shorter when it naturally coils up [7]. Shrinkage is particularly noticeable when afro-textured hair is wet or has recently been wet. The extent of shrinkage depends on the coil pattern of the hair, with more coiled textures exhibiting higher levels of shrinkage.

The curliness of hair is determined by the shape of the hair follicle. The individual hairs are never perfectly circular in shape. Instead, their cross-sections take the form of ellipses, which can range from nearly circular to distinctly flattened. Straight hair found in East Asiatic populations is produced by nearly round hair follicles, while wavy hair in European populations is a result of oval-shaped follicles. On the other hand, afro-textured hair has a flattened cross-section and is finer in texture. Its ringlets can form tight circles with diameters measuring only a few millimeters.

In terms of global distribution, East Asian-textured hair is the most prevalent among humans, while kinky hair is the least common. The predominance of East Asian hair texture is due to the large populations inhabiting the Far East and the indigenous peoples of the Americas, where this hair type is typical [8].

Evolution

According to Robbins (2012), it is proposed that afro-textured hair might have initially developed as an adaptation to provide protection against the intense UV radiation from the sun in Africa, during the early stages of human evolution [9]. The author suggests that afro-textured hair was the natural hair texture of all modern humans before the “Out-of-Africa” migration that led to the global dispersal of human populations [9].

Robbins (2012) suggests that afro-textured hair might have provided an adaptive advantage to early modern humans in Africa. The relatively sparse density and elastic helix shape of afro-textured hair create an airy effect. This characteristic could have facilitated increased circulation of cool air onto the scalp, aiding in the regulation of body temperature for hominids living in open savannah environments [9].

Afro-textured hair has distinct moisture requirements compared to straight hair and tends to shrink when dry. Instead of clinging to the neck and scalp when damp, as straighter textures do, afro-textured hair retains its springiness unless completely saturated. This trait may have been preserved and favored among various modern human populations, particularly those residing in equatorial regions like Micronesians, Melanesians, and the Negrito. The unique properties of afro-textured hair could contribute to enhanced comfort levels in tropical climates [9]. In some exceptional cases, individuals with kinky hair can also be found in populations living in temperate climate conditions, such as the indigenous Tasmanians [9].

History

Throughout history, numerous cultures in sub-Saharan Africa, like many other cultures around the world, have developed distinct hairstyles that played a crucial role in defining various aspects of identity, such as age, ethnicity, wealth, social status, marital status, religion, fertility, adulthood, and even death [10]. Hair grooming held great importance in these societies, and the way one styled their hair carried significant social implications within the community [citation needed]. People aspired to have dense, thick, clean, and well-groomed hair, as it was highly admired and considered desirable. Skilled hair groomers possessed unique expertise in creating a diverse range of hairstyles that adhered to the cultural standards prevalent in their local communities.

In traditional cultures, communal grooming served as a significant social event where women gathered to strengthen familial bonds. Historically, hair braiding was not a profession that involved monetary compensation. For instance, the Wolof tribe men from Senegal and The Gambia wore braided hairstyles when going to war, while women in mourning either kept their hair undone or styled it in a subdued manner [11]. However, since the African diaspora, especially in the 20th and 21st centuries, hair grooming has evolved into a multimillion-dollar industry in regions like the United States, South Africa, and among black African migrants in Western Europe. It was common for individuals to have a close personal relationship with their hair groomer. Grooming sessions typically involved activities such as shampooing, oiling, combing, braiding, twisting, and the addition of various hair accessories.

In the process of shampooing, black soap was widely utilized in West and Central African nations. Furthermore, palm oil and palm kernel oil were popular choices for oiling the scalp. Traditionally, shea butter has been used to moisturize and style the hair.

United States

Trans-Atlantic slave trade

Since their arrival in the Western Hemisphere before the 19th century, Diasporic Africans in the Americas have continuously experimented with various hair styling techniques. Throughout the approximately 400 years of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, which forcibly displaced over 20 million people from West and Central Africa, the ideals of beauty surrounding their hair underwent significant transformations.

As enslaved Africans, they no longer had access to the resources and tools for hair grooming that they once had in their homelands. They adapted as best they could under the circumstances, utilizing sheep-fleece carding tools to detangle their hair. Unfortunately, living conditions often led to scalp diseases and infestations. To combat these issues, enslaved individuals employed various remedies to disinfect and cleanse their scalps. Methods such as applying kerosene or cornmeal directly onto the scalp with a cloth while carefully parting the hair were common practices. Enslaved field workers often resorted to shaving their hair and wearing hats to protect their scalps from the sun’s harsh rays. On the other hand, house slaves were expected to maintain a tidy and well-groomed appearance. Men sometimes wore wigs resembling those of their masters or adopted similar hairstyles, while women typically plaited or braided their hair. During the 19th century, hair styling, particularly among women, gained more popularity. Cooking grease such as lard, butter, and goose grease were commonly used to moisturize the hair, and women occasionally employed hot butterknives to create curls [12].

Due to the prevailing belief that straight, wavy, or curly hair, commonly found among people of European descent, was more socially acceptable than kinky hair, many individuals of African descent sought ways to straighten or relax their hair. In the post-slavery era, various methods emerged for achieving this, although some were harmful and painful. One such method involved using a combination of lye, egg, and potato, which, upon contact, caused scalp burns.

Politics of kinky hair in the West

Wearing kinky hair in its natural state today represents embracing one’s natural self, and for some, it is a matter of style or personal preference. However, during the 1960s in the United States, kinky hair underwent a significant transformation and became a revolutionary political statement associated with Black Pride and Beauty. It also played a crucial role in the Black Power Movement. According to a source, hair came to symbolize either a continued move toward integration in the American political system or a growing cry for Black power and nationalism [13:51].

Before this period, the idealized image of a Black person, particularly Black women, adhered to Eurocentric standards, including hairstyles [13:29]. However, during the movement, the Black community sought to establish their own ideals and beauty standards, and hair became a central icon. It was promoted as a way of challenging mainstream standards regarding hair [14:35]. Afro-textured hair reached its peak of politicization during this time, and wearing an Afro hairstyle became a recognizable physical expression of Black pride and a rejection of societal norms [14:43].

Jesse Jackson, a political activist, emphasized that the way he wore his hair was an expression of the rebellion during that era [13:55]. Moreover, Black activists attributed political significance to straightened hair, considering it an attempt to simulate Whiteness. This act of straightening, whether chemically or through heat styling, was viewed by some as an act of self-hatred and a manifestation of internalized oppression imposed by the White-dominated mainstream media.

During this era, an African-American person’s “ability to conform to mainstream standards of beauty [was] tied to being successful.” [13]: 148. Consequently, the act of rejecting straightened hair went beyond mere hairstyling preferences; it represented a profound rejection of the belief that conforming to socially acceptable grooming practices, such as straightening hair, was the only path to presentability and success in society. Within the community, the use of pressing combs and chemical straighteners became stigmatized as symbols of oppression and the imposition of white beauty ideals. Many Black individuals sought to embrace beauty by affirming and accepting their natural physical features. A fundamental objective of the Black movement was to reach a point where Black people “were proud of black skin and kinky or nappy hair. As a result, natural hair became a symbol of that pride.”[13]: 43 .

Negative perceptions of afro-textured hair and beauty had been perpetuated across generations, leading them to become deeply ingrained in the Black community’s psyche, accepted as unquestionable truths. Opting for natural hair became a progressive statement, garnering support from some while facing opposition from others who found fault with its aesthetics or disagreed with the ideology it represented. These differences in perspective created tensions between the Black and White communities and discomfort among more conservative African-Americans.

The contemporary American society continues to engage in the politicization of kinky hair as a hairstyle. As highlighted in a source, matters related to style and hair are highly charged, involving sensitive questions about an individual’s core identity [15:34]. Whether someone chooses to wear their hair in its natural state or modifies it, all Black hairstyles carry a significant message. In various post-colonial societies, a value system is in place that promotes a ‘white bias,’ where ethnicities are judged based on their proximity to whiteness, serving as the foundation for assigning social status [15:36]. Consequently, within this value system, African cultural or physical attributes are devalued and associated with low social status, while European elements are positively valorized as tools for individual upward mobility [15:36].

This value system is further reinforced by the presence of systemic racism, which often remains concealed from public view in Western society. Racism operates by encouraging individuals to devalue their own self-identity, perpetuating a sense of pridelessness. However, the re-centering of pride becomes a necessary condition for resistance and reconstruction within a political context [15:36].

Within this system, hair plays a significant role as a prominent “ethnic signifier” that can be easily altered through cultural practices such as straightening, unlike bodily shape or facial features [15:36]. Originally, racism assigned a range of negative social and psychological connotations to kinky hair, burdening it with problematic meanings [15:37]. Ethnic minorities were encouraged to modify easily manipulable traits, like hair, in order to assimilate into a dominant Eurocentric society. However, natural hairstyles like the Afro and dreadlocks emerged as counter-politicization against the devaluation of ethnic identity, redefining Blackness as a positive attribute [15]. By embracing their hair’s natural texture, individuals with kinky hair reclaim agency in determining the value and politics surrounding their own hair.

Moreover, wearing hair naturally engenders a new debate within the community: Does one’s decision to maintain straightened hair, for example, make them less “Black” or less proud of their heritage compared to those who choose to wear their hair in its natural state? This ongoing debate sparks extensive discussions and disputes within the community, creating a social division between those who opt for natural hair and those who do not.

Emancipation and post-Civil War

Following the American Civil War and the emancipation of African-Americans, many individuals migrated to larger towns and cities, where they were exposed to new styles and influences. In the 19th century, women leaders of that era showcased a range of natural hair styles, as depicted in the accompanying photos. However, there were also those who chose to straighten their hair in order to conform to White beauty ideals. This decision was motivated by a desire to succeed and to avoid mistreatment, including legal and social discrimination.

To achieve straight hair, some individuals, primarily women but also a smaller number of men, resorted to lightening their hair with household bleach. The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the development of various caustic products that incorporated bleaching agents, including laundry bleach, specifically formulated for application to afro-textured hair. These products emerged in response to the growing demand for fashion options among African-Americans. The straightening process involved the use of creams and lotions in conjunction with hot irons.During this period, African Americans sought diverse methods to adapt their hairstyles, reflecting their evolving fashion choices and aspirations. It is important to recognize the complex historical context that influenced these decisions regarding hair care and styling.

During the late 19th century, the Black hair care industry was initially controlled by White-owned businesses. However, African-American entrepreneurs played a pivotal role in revolutionizing the field. Visionaries like Annie Turnbo Malone, Madam C. J. Walker, Madam Gold S.M. Young, Sara Spencer Washington, and Garrett Augustus Morgan emerged as key figures by inventing and promoting chemical and heat-based applications to modify the natural tightly curled texture of Black hair. Their innovative products quickly gained popularity, enabling them to dominate the Black hair care market.

In 1898, Anthony Overton established a hair care company that introduced saponified coconut shampoo and AIDA hair pomade. These products catered to the needs of both men and women. Men, in particular, embraced pomades and various other grooming products to achieve the desired aesthetic appearance that was widely accepted at the time.

In the 1930s, a hair straightening technique called conking emerged as an inventive method for African American men in the United States to achieve straight hair, as vividly described in The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Meanwhile, women during that era often opted to wear wigs or use hot combs to temporarily imitate a straight hairstyle, without permanently altering their natural curl pattern. The conk hairstyle remained popular until the 1960s but was achieved through the application of a harsh mixture containing lye, eggs, and potatoes. Unfortunately, this toxic blend caused immediate scalp burns and inflicted considerable pain.

Black-owned businesses in the hair-care industry played a pivotal role in generating employment opportunities for numerous African-Americans, while also making substantial contributions to the African-American community [16]. During this era, a significant number of African-Americans emerged as owners and operators of successful beauty salons and barbershops. These establishments provided a range of services, including permanents, hair-straightening, cutting, and styling, catering to both White and Black customers. Additionally, barber shops became popular gathering places for men to maintain their well-groomed appearance, with some Black barbers even developing an exclusive clientele of White elites, often in partnership with hotels or clubs. Notably, media portrayals during this time tended to uphold the ideals of European beauty prevalent in the majority culture, even when featuring African-Americans [16].

African-Americans took the initiative to organize and support their own beauty events, where winners—some of mixed race and many sporting straight hair styles—graced the pages of Black magazines and featured in product advertisements. During the early 20th century, media representations of traditional African hair styles, like braids and cornrows, were often associated with impoverished African-Americans residing in rural areas. However, in the initial decades of the Great Migration, when a significant number of African-Americans left the South to seek better opportunities in industrial cities of the North and Midwest, many individuals aimed to distance themselves from this rural stereotype [17].

Scholars engage in ongoing debates surrounding the origins of hair-straightening practices within the Black community, questioning whether they emerged due to a desire to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards or as part of individual fashion experimentation and evolving styles. Some argue that slaves and later African-Americans internalized the biases of European slaveholders and colonizers, who viewed most slaves as inferior due to their non-citizen status. Ayana Byrd and Lori Tharp hold the belief that the preference for Eurocentric beauty ideals continues to influence the Western world [18].

Rise of Black pride

The journey of Afro hair has witnessed numerous transformations throughout history. The institution of slavery significantly impacted the ebb and flow of pride associated with African-Americans’ hair. Lisa Jones, in her essay titled “Hair Always and Forever” beautifully articulates the profound symbolism of Black hair in understanding American history. She asserts that the experiences of Black people, including the involuntary passage through slavery, its enduring consequences, and the resilience exhibited, can be encapsulated in the narratives surrounding their hair. Drawing inspiration from Jamaica Kincaid, who exclusively writes about a character named Mother, Jones focuses her writing solely on hair—exploring the ways in which it is styled, treated, and the underlying motivations. In doing so, she believes that the exploration of hair is sufficient to capture the complexities and significance of the African-American experience [19].

According to Cheryl Thompson, hairstyles in 15th-century Africa served as indicators of various aspects such as marital status, age, religion, ethnic identity, wealth, and social standing within the community [10]. Thompson emphasizes that for young Black girls, hair holds a profound significance—it is not merely something to play with but a medium of communication that conveys messages not only to the outside world but also about their own self-perception [10]. In the 1800s and early 1900s, Marcia Wade Talbert notes that nappy, kinky, and curly hair was often stigmatized as inferior, unattractive, and unkempt when compared to the flowing and voluminous hair of other cultures [20]. The demand for chemical relaxers increased during this period, which often contained harmful substances like sodium hydroxide (lye) or guanidine hydroxide. These relaxers, as highlighted by Gheni Platenurg, had detrimental effects on hair health, including breakage, thinning, slowed growth, scalp damage, and even hair loss [21]. The article “Black Women Returning to Their Natural Hair Roots” delves into this topic further.

In the United States, the civil rights movement, along with the Black power and Black pride movements of the 1960s and 1970s, had a profound impact on African-Americans, inspiring them to embrace traditional African hairstyles as a means of expressing their political commitments. The Afro hairstyle emerged as a symbol of Black African heritage, famously associated with the empowering phrase “Black is beautiful”. Angela Davis, for instance, wore her Afro as a political statement, sparking a movement towards embracing natural hair. This movement had a significant influence on an entire generation, including influential figures like Diana Ross, whose iconic Jheri curls became synonymous with the 1980s.

Since the late 20th century, Black individuals have continued to explore a diverse range of hairstyles tailored specifically for kinky hair, such as cornrows, locks, braids, twists, and short cropped cuts. The popularity of natural hair has been fostered by the rise of online platforms and blogs dedicated to discussing and celebrating natural hairstyles, including Black Girl Long Hair (BGLH), Curly Nikki, and Afro Hair Club. Furthermore, with the emergence of hip-hop culture and the influence of Jamaican elements like reggae music, these hairstyles have transcended racial boundaries, leading to a growing number of non-Black individuals embracing these styles. This cultural shift has also given rise to a new market for hair products catering to the specific needs of Afro-textured hair, as evidenced by the introduction of products like “Out of Africa” shampoo.

The popularity of natural hair has experienced fluctuations over time. In the early 21st century, a significant portion of African-American women continued to straighten their hair using relaxers, either through chemical-based or heat-based processes. However, the prolonged use of such chemicals or heat can lead to overprocessing, breakage, and thinning of the hair. Rooks (1996) argues that hair-care products marketed by white-owned companies in African-American publications since the 1830s, which promote hair straightening, perpetuate unrealistic and unattainable beauty standards [22].

Between 2010 and 2015, sales of relaxers among African-American women witnessed a significant decline. Many women chose to embrace their natural hair texture, abandoning relaxers and returning to their roots. Celebrities like Esperanza Spalding, Janelle Monáe, and Solange Knowles have embraced natural hair looks, further inspiring this trend. During this time, the number of natural-hair support groups has increased, indicating a growing acceptance and celebration of natural hair. This shift represents a significant change, as women are encouraging both themselves and their children to accept and embrace their natural hair, marking a new era of self-acceptance [23]. Research indicates a decline in relaxer sales, from $206 million in 2008 to $156 million in 2013, while sales of products catering to styling natural hair continued to rise. Chris Rock’s documentary, “Good Hair,” shed light on the lengths many women went through to conform to the “European standard” of hair, such as expensive weaves and time-consuming relaxer treatments. The documentary suggests that Black women have reached a point where they find these practices to be excessive and have opted for a more accepting approach towards their natural hair [24].

Modern perceptions and controversies

Black hairstyles have played a significant role in expressing African-American identity, but they have also faced scrutiny and disapproval throughout history.

In 1971, Melba Tolliver, a correspondent for WABC-TV, made national headlines when she wore an Afro while covering the wedding of Tricia Nixon Cox, the daughter of President Richard Nixon. Tolliver faced backlash from the station, which threatened to remove her from the air. However, the story gained widespread attention, bringing the issue to the forefront [28].

Another incident occurred in 1981 when Dorothy Reed, a reporter for KGO-TV, the ABC affiliate in San Francisco, was suspended for wearing cornrows with beads on the ends. KGO deemed her hairstyle “inappropriate and distracting.” This sparked a public dispute, with the NAACP organizing a demonstration outside the station. After two weeks of negotiations, Reed and the station reached an agreement. The company compensated her for the lost salary, and she removed the colored beads. Reed returned to the air, still sporting braided hair but without the beads [29].

In 1998, an incident involving Ruth Ann Sherman, a young White teacher in Bushwick, Brooklyn, gained national attention. Sherman introduced her students to the book “Nappy Hair” by African-American author Carolivia Herron. While the book had received three awards, some members of the community criticized Sherman, believing that it perpetuated a negative stereotype. However, the majority of her students’ parents supported her decision [30].

On April 4, 2007, radio talk-show host Don Imus sparked controversy when he referred to the Rutgers University women’s basketball team, who were playing in the Women’s NCAA Championship game, as a group of “nappy-headed hos” during his show, Imus in the Morning. Imus’s producer, Bernard McGuirk, also made derogatory remarks comparing the game to Spike Lee’s film School Daze. After facing widespread criticism, Imus issued an apology two days later. However, CBS Radio ultimately decided to cancel Imus’s morning show on April 12, 2007, leading to the termination of both Imus and McGuirk [30].

In August 2007, The American Lawyer magazine reported an incident involving an unnamed junior staffer at Glamour Magazine. During a presentation on the “Do’s and Don’ts of Corporate Fashion” for Cleary Gottlieb, a New York City law firm, the staffer made derogatory comments about Black women wearing natural hairstyles in the workplace. She described such hairstyles as “shocking,” “inappropriate,” and “political.” Both the law firm and Glamour Magazine issued apologies to the staff in response to the incident [31][32].

In 2009, Chris Rock released the documentary film “Good Hair,” which delves into various aspects of African-American hair. The film examines the hair styling industry, the range of hairstyles accepted in society for African-American women, and their connection to African-American culture.

Ajuma Nasenyana, a Kenyan model, has voiced her criticism of a prevailing trend in Kenya that rejects the natural beauty standards of indigenous Black Africans in favor of those from other communities. In a 2012 interview with the Kenyan newspaper, the Daily Nation, she expressed her concerns, stating:

”It seems that the world is conspiring in preaching that there is something wrong with Kenyan ladies’ kinky hair and dark skin […] Their leaflets are all about skin lightening, and they seem to be doing good business in Kenya. It just shocks me. It’s not OK for a Caucasian to tell us to lighten our skin […] I have never attempted to change my skin. I am natural. People in Europe and America love my dark skin. But here in Kenya, in my home country, some consider it not attractive” [33].

In November 2012, American actress Jada Pinkett Smith took to Facebook to defend her daughter Willow’s hairstyle after it received criticism for being “unkempt”. Pinkett Smith expressed her belief that even young girls should not be constrained by society’s predetermined notions of how they should look. She stated, “Even little girls should not be a slave to the preconceived ideas of what a culture believes a little girl should be” [34].

In 2014, Stacia L. Brown shared her personal experience and reflections on the significance of her hairstyle in an article titled “My Hair, My Politics“. She recounts her decision to undergo the “Big Chop“, cutting off her relaxed or processed hair, and how a few months later, as she entered the job market, she became anxious about how her natural hair would be perceived during job interviews. Fortunately, she did not face any discriminatory comments about her hair from interviewers.

Stacia then discusses the symbolic nature of wearing her natural hair as a political statement, relating it to her own concerns about how her hair might be viewed as a potential “professional liability. ” She highlights the contrast between her natural hair, which is easier to style, and her relaxed hair, which is more widely accepted. Stacia also provides examples of workplace discrimination targeting Black hairstyles, such as the Congressional Black Caucus challenging the U.S. military’s grooming policies that banned cornrows, twists, and dreadlocks [35](Brown 17).

Additionally, she mentions a controversy from the same year involving the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) disproportionately subjecting black women with Afros to pat-downs, a practice that only came to a halt a few months prior to her article’s publication after the ACLU of Northern California filed a complaint in 2012 and reached an agreement with the agency [35](Brown 17).

Individuals with kinky hair have different perspectives on how they choose to style their hair. Some may prefer hairstyles that highlight and celebrate their racial background, while others may opt for hairstyles that align with more European standards.

In 2016, an article titled “Beauty as violence: ”beautiful hair and the cultural violence of identity erasure” discussed a study conducted at a South African University with 159 African female students. The study involved presenting the participants with 20 pictures showcasing different styles of afro-textured hair, which they categorized into four types: African Natural Hair, Braided African Natural Hair, African Natural Augmented Braid, and European/Asian Hairstyles. The findings revealed that only 15.1% of the respondents identified the category of African natural hair as beautiful [36](Oyedemi 546). Braided natural hair received 3.1% of the votes, braided natural augmented hair had 30.8%, and European/Asian hair garnered 51% of the votes. Author Toks Oyedemi, in reference to these findings, highlights how this evidence showcases the cultural violence of symbolic indoctrination. It perpetuates the perception that beautiful hair is mainly associated with a European/Asian texture and style, creating a trend where such hair is considered more beautiful and preferable compared to natural African hair [36](Oyedemi 546). This article sheds light on the unfortunate truth about how African girls feel about their own hair, reflecting a lack of self-acceptance.

However, in another experiment conducted in the United States, the perception is reversed.

In a study published in 2016, titled “African American Personal Presentation: Psychology of Hair and Self Perception“, data from five urban areas in the United States and females aged 18-65 were analyzed. The study aimed to understand how African American women perceive beauty and their hair by examining locus of control and self-esteem. The findings revealed that there was a positive correlation between a high internal locus of control and wearing hair in its natural state, indicating that American women feel empowered when embracing their natural hair texture and style [37](Ellis-Hervey 879).

In response to discriminatory practices, significant strides have been made to protect individuals’ rights to wear their natural hair. In 2019, the California State Assembly unanimously passed the CROWN Act, a law designed to prohibit discrimination based on hairstyle and hair texture [38]. This led to the introduction of similar laws in other states, including New York, New Jersey, Washington, Maryland, Virginia, and Colorado, in the following years [39]. Moreover, in 2022, the US House of Representatives passed a similar law known as the CROWN Act of 2022 [40][41]. These legislative actions aim to combat hair-based discrimination and promote inclusivity and acceptance of diverse hairstyles.

In other diasporic African populations

In the 19th century, the teachings of Jamaican political leader Marcus Garvey had a profound impact on rejecting European beauty standards in the West Indies. This led to the emergence of the Rastafari movement in the 20th century, which advocated for the rejection of these standards and embraced natural aesthetics. Within the Rastafari movement, the growth of freeform dreadlocks has been viewed as a symbol of spiritual enlightenment, influenced by the Biblical Nazirite oath. The Rastafari movement’s influence has been instrumental in popularizing dreadlocks throughout the Caribbean and the global African diaspora, to the extent that the term “rasta” has become synonymous with an individual who wears dreadlocks. Today, dreadlocks are commonly seen among Afro-Caribbeans and Afro-Latin Americans, reflecting the cultural and spiritual significance associated with this hairstyle.

Styling

Throughout time, natural hair styles and trends have undergone changes influenced by factors such as media, cultural shifts, and political climates [14]. In the United States, the care and styling of natural Black hair have evolved into a significant industry. There are now numerous salons and beauty supply stores dedicated specifically to serving clients with natural afro-textured hair. This focus on catering to the unique needs of afro-textured hair reflects the growing recognition and appreciation for diverse hair types and the increasing demand for products and services tailored to natural hair care.

The Afro is a distinctive hairstyle characterized by a voluminous, often spherical shape formed by afro-textured hair. It gained significant popularity during the Black Power movement. Alongside the classic Afro, there are various variants that emerged over time. One such variation is the “afro puffs”, which combines elements of both pigtails and the Afro style. Another variant involves using a blow dryer to create a flowing, mane-like effect with the Afro.

In the 1980s, the “hi-top fade” hairstyle was commonly seen among African-American men and boys. However, its popularity has since been replaced by other styles such as the 360 waves, characterized by wave-like patterns in the hair, and the Caesar haircut, a short, evenly trimmed hairstyle.

There are several other popular styles for afro-textured hair, including plaits or braids, the two-strand twist, and basic twists. These styles can further develop into manicured dreadlocks if the hair is allowed to naturally interlock and form a specific pattern. Basic twists encompass techniques like finger-coils and comb-coil twists. Dreadlocks, also known as “dreads”, “locks”, or “locs” can be achieved by allowing the hair to naturally intertwine from an Afro. An alternative method called “Sisterlocks”, which is a trademarked technique, creates very neat micro-dreadlocks [42]. Additionally, there are options such as faux locs, which are synthetic dreadlocks created using extensions.

Manicure locks, also known as salon locks or fashion locks, offer a wide range of styling possibilities through strategic parting, sectioning, and creating patterns with the dreads. Popular styles include cornrows, braid-outs or “lock crinkles”, basket weaves, and pipe-cleaner curls. Other options include various dreadlocked mohawks or lock-hawks, braided buns, and creative combinations of different style elements.

In addition to these options, natural hair can also be styled into Bantu knots. This involves sectioning the hair with square or triangular parts and fastening it into tight buns or knots on the head. Bantu knots can be created using either loose natural hair or dreadlocks [44]. Furthermore, when braided flat against the scalp, natural hair can be worn as basic cornrows or fashioned into countless artistic patterns, allowing for creative and expressive styles.

Other natural hair styles include the “natural” or “mini-fro”, which is a close-cropped hairstyle, as well as microcoils for short hair. The twist-out and braid-out techniques involve twisting or braiding the hair and then unraveling for a textured look. Brotherlocks and Sisterlocks are specific methods for creating uniform-sized dreadlocks. The fade style is popular among men, while twists come in variations such as Havana, Senegalese, and crochet twists. Faux locs imitate the appearance of dreadlocks using synthetic hair extensions. Braids encompass styles like Ghana braids, box braids, crochet braids, and cornrows. Bantu knots create small coiled knots, while bubbles involve using hair elastics to create rounded sections. Custom wigs and weaves offer versatility, and different styles can be combined, such as cornrows and Afro-puffs.

Most Black hairstyles involve sectioning the natural hair before styling [45]. However, it’s important to note that excessive braiding, tight cornrows, relaxing treatments, and vigorous dry-combing of kinky hair can cause damage to both the hair and scalp. These practices have been associated with conditions like alopecia, excessive dryness of the scalp, and scalp bruises. To maintain healthy hair, it is recommended to keep the hair well-moisturized, regularly trim the ends, and minimize the use of heat styling tools. By following these practices, breakage and split ends can be prevented, promoting overall hair health.

Reference

- Loussouarn G (August 2001). “African hair growth parameters”. Br. J. Dermatol. 145 (2): 294–7. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04350.x. PMID 11531795. S2CID 29264439.

- Walker, Andre (2 May 1997). Andre Talks Hair. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0684824567.

- “hot comb – Wari LACE”. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Naanis, Naturals. “LOIS Hair System: What Type of African/Black Hair Do You Have?”. From Grandma’s Kitchen. Archived from the original on 29 October 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- Franbourg; et al. (2007). “Influence of Ethnic Origin of Hair on Water-Keratin Interaction”. In Enzo Berardesca; Jean-Luc Lévêque; Howard I. Maibach (eds.). Ethnic Skin and Hair. New York: Informa Healthcare. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8493-3088-9. OCLC 70218017.

- Khumalo NP, Gumedze F (September 2007). “African hair length in a school population: a clue to disease pathogenesis?”. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 6 (3): 144–51. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00326.x. PMID 17760690. S2CID 19046470.

- “Shrinkage In Natural Curly Black Hair—How to Work with It”. Blackhairinformation.com. 14 February 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- “Hair Science”. Hair Science. 1 February 2005. Archived from the original on 25 August 2004. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- Robbins, Clarence R. (2012) Chemical, Weird and Physical Behavior of Human Hair, p. 181, ISBN 3642256112

- Thompson, Cheryl (2008). “Black Women and Identity: What’s Hair Got to do with it?”. Michigan Feminist Studies. 22 (1). hdl:2027/spo.ark5583.0022.105.

- Jahangir, Rumeana (31 May 2015). “How does black hair reflect black history?”. BBC News. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Hargro, Brina. “Hair Matters: African American Women and the Natural Hair Aesthetic”. ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. Georgia State University. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Tharps, Lori; Byrd, Ayana (12 January 2002). Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin. ISBN 9780312283223.

- Banks, Ingrid (2000). Hair matters : beauty, power, and Black women’s consciousness. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814713372. OCLC 51232344.

- Mercer, Kobena (1987). “Black hair/style politics” (PDF). New Formations. 3: 33–54.

- Edmondson, Vickie Cox; Carroll, Archie B. (1999). “Giving Back: An Examination of the Philanthropic Motivations, Orientations and Activities of Large Black-Owned

- Businesses”. Journal of Business Ethics. 19 (2): 171–179. doi:10.1023/A:1005993925597. JSTOR 25074086. S2CID 15255094.

- Sherrow, Victoria (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-313-33145-9. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

Byrd, Ayana D.; Tharps, Lori L. (2001). Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America. St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-312-28322-3. - Johnson, Dianne (2004). “‘She’s grown dreadlocks’: the fiction of Angela Johnson”. World Literature Today. 78 (3–4): 75–78. doi:10.2307/40158506. JSTOR 40158506. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016.

- Wade Talbert, Marcia (22 February 2011). “Natural Hair and Professionalism”. Black Enterprise.

- Platenburg, Gheni “Black Women Returning to Their Natural Roots”. Victoria Advocate (TX) 3 March 2011. 10 April 2015.

- Rooks, Noliwe M. (1996). Hair raising : beauty, culture, and African American women. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780585098272. OCLC 44964950.

- Shropshire, Terry (2015-04-02) “Black Hair Relaxer Sales are Slumping Because Of This”. atlantadailyworld.com

- Rock, Chris Good Hair Produced by Chris Rock Productions and HBO Films. 10 April 2015.

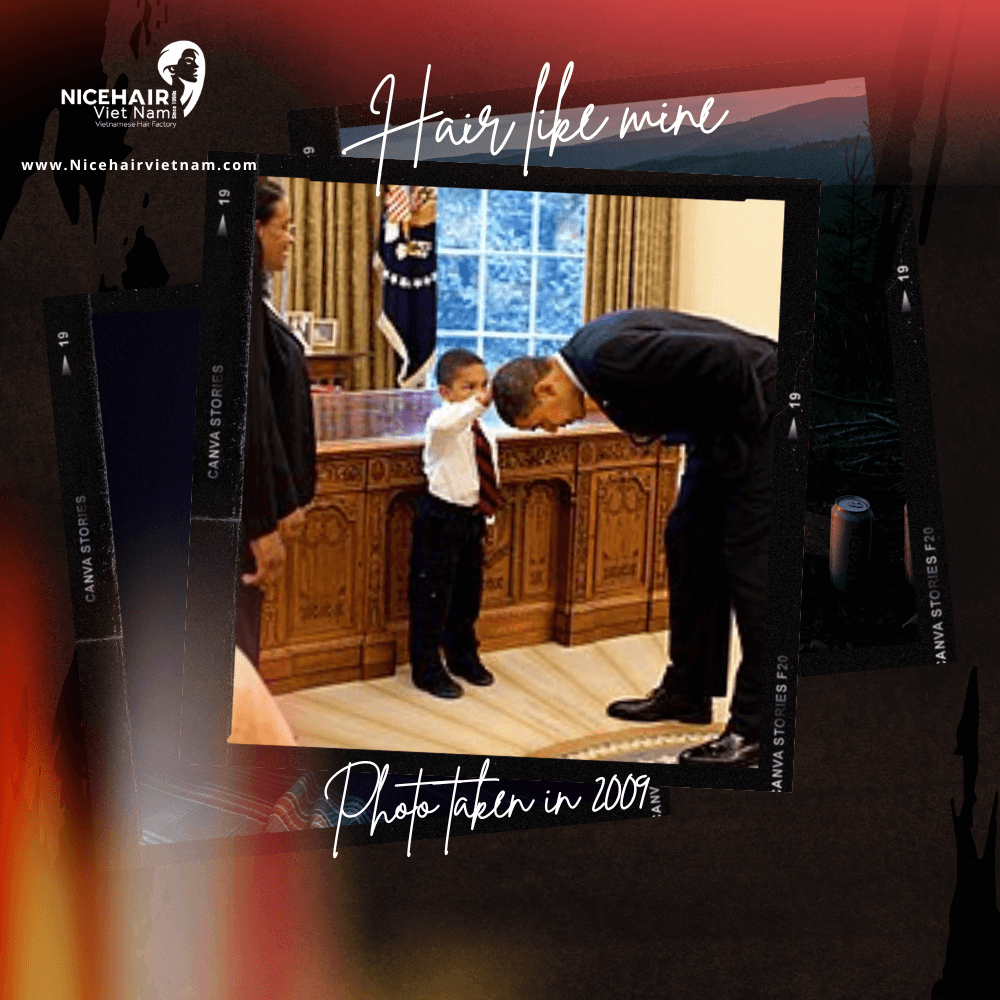

- “Boy who touched Obama’s hair: Story behind White House photo is probably in your inbox”. The Cutline. Yahoo! News.

- Calmes, Jackie (23 May 2012). “Indelible Image of a Boy’s Pat on Obama’s Head Hangs in White House”. The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Jones, Jonathan (25 May 2012). “Barack Obama bows to the significance of his ethnicity”. The Guardian. London.

- Douglas, William (9 October 2009). “For Many Black Women, Hair Tells the Story of Their Roots”. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- “1981: Television reporter Dorothy Reed is suspended for wearing her hair in cornrows”. Archived from the original on 8 September 2002. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- Leyden, Liz (3 December 1998). “N.Y. Teacher Runs Into a Racial Divide”. Washington Post. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- “‘Glamour’ Editor To Lady Lawyers: Being Black Is Kinda A Corporate ‘Don’t'”. Jezebel. Gawker Media. 14 August 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- “Faux Locs”. Types of Faux Locs for African Hair. 7 September 2007. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- Danielle, Britni. “Kenyan model Ajuma Nasenyana fights skin lightening and European standards of beauty”. Clutch Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Johnson, Craig (28 November 2012). “Jada blasts Willow hair critics: It’s her choice”. HLN TV. Turner Broadcasting. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Brown, Stacia (2015). “My Hair, My Politics”. New Republic. Vol. 246. pp. 16–17. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020.

- Oyedemi, Toks (2016). “Beauty as violence: ‘beautiful hair’ and the cultural violence of identity erasure”. Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture. 22 (5): 537–553. doi:10.1080/13504630.2016.1157465. S2CID 147092123.

- Ellis-Hervey, Nina; et al. (2016). “African American Personal Presentation: Psychology of Hair and Self-Perception”. Journal of Black Studies. 47 (8): 869–882. doi:10.1177/0021934716653350. S2CID 148398852.

- “California becomes first state to ban discrimination against natural hair”. CBS News. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- “U.S. Congress passes CROWN Act”. Congresswoman Robin Kelly. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- America, Good Morning. “National Crown Day: 13 states have passed laws to ban natural hair discrimination”. Good Morning America. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- “Huntington City Council members pass CROWN Act”. MSN. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Irons, Meghan (6 January 2008). “Black women find freedom with new ‘do”. Boston Globe. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Pometsey, Olive (15 June 2018). “Just A Super Useful Guide To Getting Faux Locs”. ELLE. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- “The Bantu Knots Hairstyle: A Beautiful Controversy”. www.curlcentric.com. 21 October 2017.

- “Braiding ‘can lead to hair loss'”. BBC News. 24 August 2007.